Credit: Microsoft

If you’ve been following our coverage for the last few years, you’ll already know that 2025 is the year that Windows 10 died. Technically.

“Died,” because Microsoft’s formal end-of-support date came and went on October 14, as the company had been saying for years. “Technically,” because it’s trivial for home users to get another free year of security updates with a few minutes of effort, and schools and businesses can get an additional two years of updates on top of that, and because load-bearing system apps like Edge and Windows Defender will keep getting updates through at least 2028 regardless.

But 2025 was undoubtedly a tipping point for the so-called “last version of Windows.” StatCounter data says Windows 11 has overtaken Windows 10 as the most-used version of Windows both in the US (February 2025) and worldwide (July 2025). Its market share slid from just over 44 percent to just under 31 percent in the Steam Hardware Survey. And now that Microsoft’s support for the OS has formally ended, games, apps, and drivers are already beginning the gradual process of ending or scaling back official Windows 10 support.

Windows 10 is generally thought of as one of the “good” versions of Windows, and it was extremely popular in its heyday: the most widely used version of Windows since XP. That’s true even though many of the annoying things that people complain about in Windows 11 started during the Windows 10 era. Now that it’s time to write Windows 10’s epitaph, it’s worth examining what Microsoft got right with Windows 10, how it laid the groundwork for many of the things people dislike about Windows 11, and how Microsoft has made all of those problems worse in the years since Windows 11 first launched.

Windows 10 did a lot of things right

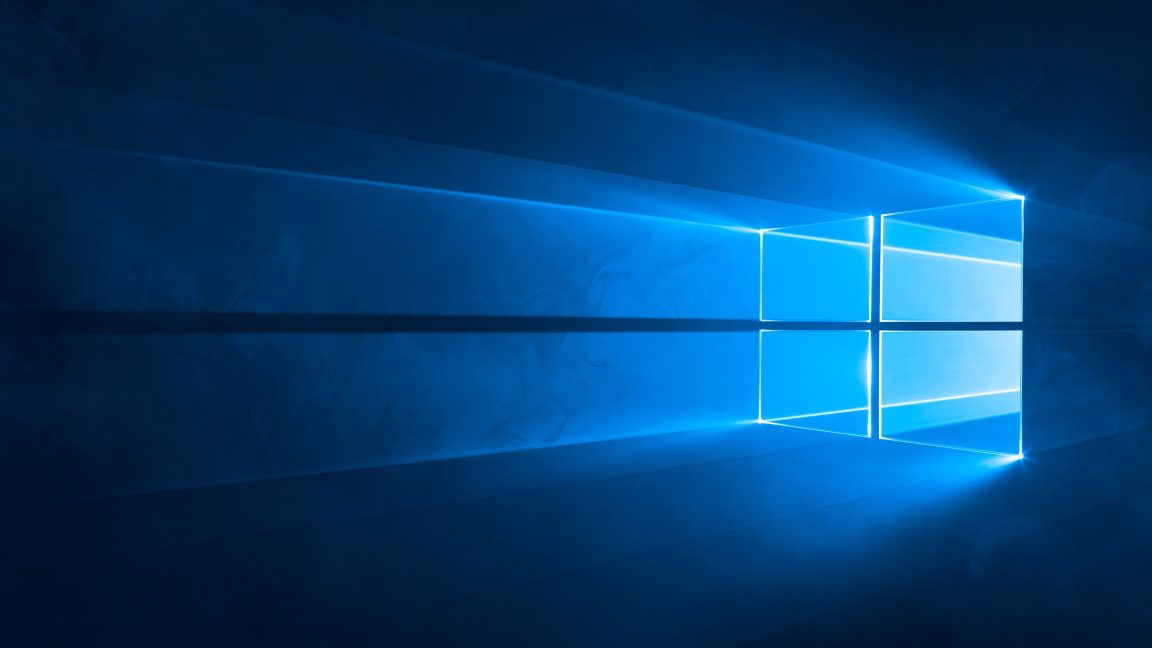

The Start menu in the first release of Windows 10. Windows 10 got a lot of credit for not being Windows 8 and for rolling back its most visible and polarizing changes.

Like Windows 7, Windows 10’s primary job was to not be its predecessor. Windows 8 brought plenty of solid under-the-hood improvements over Windows 7, but it came with a polarizing full-screen Start menu and a touchscreen-centric user interface that was an awkward fit for traditional desktops and laptops.

And the biggest thing it did to differentiate itself from Windows 8 was restore a version of the traditional Start menu, altered from its Windows XP or Windows 7-era iterations but familiar enough not to put people off.

Windows 10 also adopted a bunch of other things that people seemed to like about their smartphones—it initially rolled out as a free upgrade to anyone already running Windows 7 or Windows 8, and it ran on virtually all the same hardware as those older versions. It was updated on a continuous, predictable cadence that allowed Microsoft to add features more quickly. Microsoft even expanded its public beta program, giving enthusiasts and developers an opportunity to see what was coming and provide feedback before new features were rolled out to everybody.

Windows 10 also hit during a time of change at Microsoft. Current CEO Satya Nadella was just taking over from Steve Ballmer, and as part of that pivot, the company was also doing things like making its Office apps work on iOS and Android and abandoning its struggling, proprietary browser engine for Edge. Nadella’s Microsoft wanted you to be using Microsoft products (and ideally paying for a subscription to do so), but it seemed more willing to meet people where they were rather than forcing them to change their behavior.

That shift continued to benefit users throughout the first few years of Windows 10’s life. Developers benefited from the introduction and continuous improvement of the Windows Subsystem for Linux, a way to run Linux and many of its apps and tools directly on top of Windows. Microsoft eventually threw out its struggling in-house browser engine for a new version of the Edge browser built on Chromium—we can debate whether Chromium’s supremacy is a good thing for an open, standard-compliant Internet, but switching to a more compatible rendering engine and an established extension ecosystem was absolutely the more user-friendly choice. Both projects also signaled Microsoft’s growing engagement with and contributions to open-source projects, something that would have been hard to imagine during the company’s closed-off ’90s and ’00s.

Windows 10 wasn’t perfect; these examples of what it did right are cherry-picked. But part of the operating system’s reputation comes from the fact that it was originally developed as a response to real complaints and rolled out in a way that tried to make its changes and improvements as widely accessible as possible.

But Windows 10 laid the groundwork for Windows 11’s problems

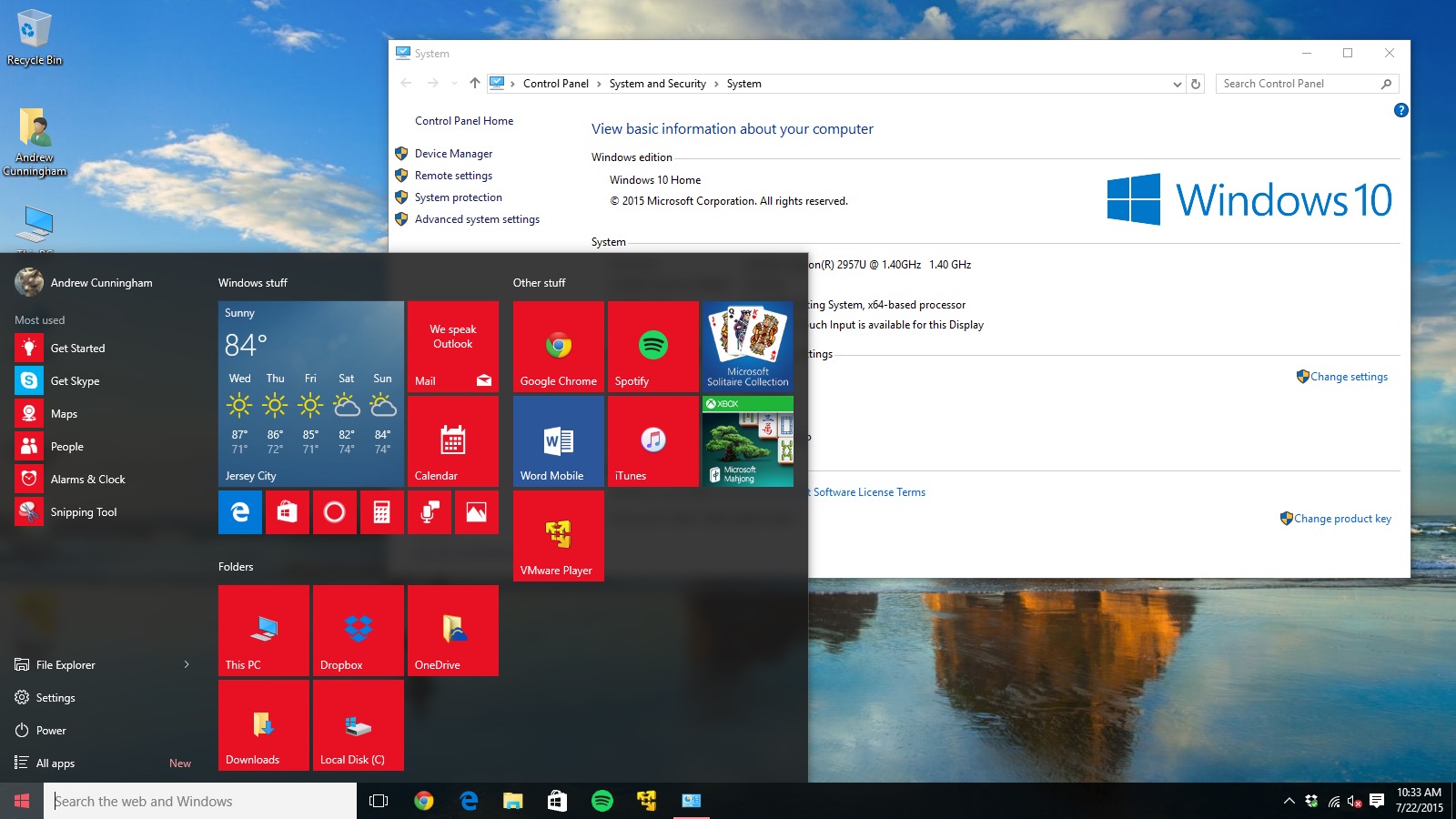

Windows 10 asked you to sign in with a Microsoft account, but for most of the operating system’s life, it was easy to skip this using visible buttons in the UI. Windows 10 began locking this down in later versions; that has continued in Windows 11, but it didn’t originate there.

Credit: BTNHD

As many things as Windows 10 did relatively well, most of the things people claim to find objectionable about Windows 11 actually started happening during the Windows 10 era.

Right out of the gate, for example, Windows 10 wanted to collect more information about how people were using the operating system—ostensibly in the name of either helping Microsoft improve the OS or helping “personalize” its ads and recommendations. And the transition to the “software-as-a-service” approach helped Windows move faster but also broke things, over and over again—these kinds of bugs have persisted on and off into the Windows 11 era despite Microsoft’s public beta programs.

Windows 10 could also get pushy about other Microsoft products. Multiple technologies, like the original Edge and Cortana, were introduced, pushed on users, and failed. The annoying news and weather widget on the taskbar was a late addition to Windows 10; advertisements and news articles could clutter up its lock screen. Icons for third-party apps from the Microsoft Store, many of them low-rent, ad-supported time-waster games, were added to the Start menu without user consent. Some users of older Windows versions even objected to the way that the free Windows 10 upgrade was offered—the install files would download themselves automatically, and it could be difficult to make the notifications go away.

Even the mandatory Microsoft Account sign-in, one of the most frequently complained-about aspects of Windows 11, was a Windows 10 innovation—it was easier to circumvent than it is now, and it was just for the Home edition of the software, but in retrospect, it was clearly a step down the road that Windows 11 is currently traveling.

Windows 11 did make things worse, though

But many of Windows 11’s annoyances are new ones. And the big problem is that these annoyances have been stacked on top of the annoying things that Windows 10 was already doing, gradually accumulating to make the new PC setup process go from “lightly” to “supremely” irritating.

The Microsoft Account sign-in requirement is ground zero for a lot of this since signing in with an account unlocks a litany of extra ads for Microsoft 365, Game Pass, and other services you may or may not need or want. Connecting to the Internet and signing in became a requirement for new installations of both the Home and the Pro versions of Windows 11 starting with version 22H2, and while workarounds existed then and continue to exist now, you have to know about them beforehand or look them up yourself—the OS doesn’t offer you an option to skip. Microsoft will also apparently be closing some of these loopholes in future updates, making circumvention even more difficult.

And if getting through those screens when setting up a new PC wasn’t annoying enough, Windows 11 will regularly remind you about other Microsoft services again through its Second Chance Out-Of-Box Experience screen, or SCOOBE. This on-by-default “feature” has offered to help me “finish setting up” Windows 11 installations that are years old and quite thoroughly set up. It can be turned off via a buried checkbox in the Notifications settings, but removing it or making it simpler to permanently dismiss from the SCOOBE screen itself would be the more user-friendly change, especially since Microsoft already bombards users with “helpful reminders” about many of these same services via system notifications.

Microsoft’s all-consuming pivot to generative AI also deserves blame. Microsoft’s Copilot push hasn’t stopped with the built-in app that gets a position of honor on the default taskbar—an app whose appearance and functionality have completely changed multiple times in the last couple of years as Microsoft has updated it. Microsoft changed the default Windows PC keyboard layout for the first time in 30 years to accommodate Copilot, and Copilot-branded features have landed in every Windows app from Word to Paint to Edge to Notepad. Sometimes these features can be uninstalled or turned off; sometimes they can’t.

It’s not just that Microsoft is squeezing generative AI into every possible nook and cranny in Windows; it’s that there seems to be no feature too intrusive or risky to make the cutoff. Microsoft nearly rolled out a catastrophically insecure version of Recall, a feature for some newer PCs that takes screenshots of your activity and records it for later reference; Microsoft gave its security an overhaul after a massive outcry from users, media, and security researchers, but Recall still rolled out.

The so-called “agentic” AI features that Microsoft is currently testing in Windows come with their own documented security and privacy risks, but their inclusion in Windows is essentially a foregone conclusion because Microsoft executives are constantly talking about the need to develop an “agentic OS.” There’s a fine line between introducing new software features and forcing people to use them, and I find that Microsoft’s pushiness around Windows 11’s AI additions falls on the wrong side of that line for me pretty much every single time.

Finally, while Windows 10 ran on anything that could run Windows 7 or 8, Windows 11 came with new system requirements that excluded many existing, functional PCs. The operating system can be installed unofficially on PCs that are several years older than the official cutoff, but only if you’re comfortable with the risks and you know how to get around the system requirements check.

Using people’s PCs as billboards to sell them new PCs feels tacky at best.

Credit: Kyle Orland

I find the heightened requirements—implemented to improve security, according to Microsoft—to be more or less defensible. TPM modules enable seamless disk encryption, Secure Boot protects from threats that are otherwise invisible and hard to detect, and CPU makers like Intel and AMD only commit to supporting older processors with firmware-level security patches for so long, which is important in the era of hardware-level security exploits.

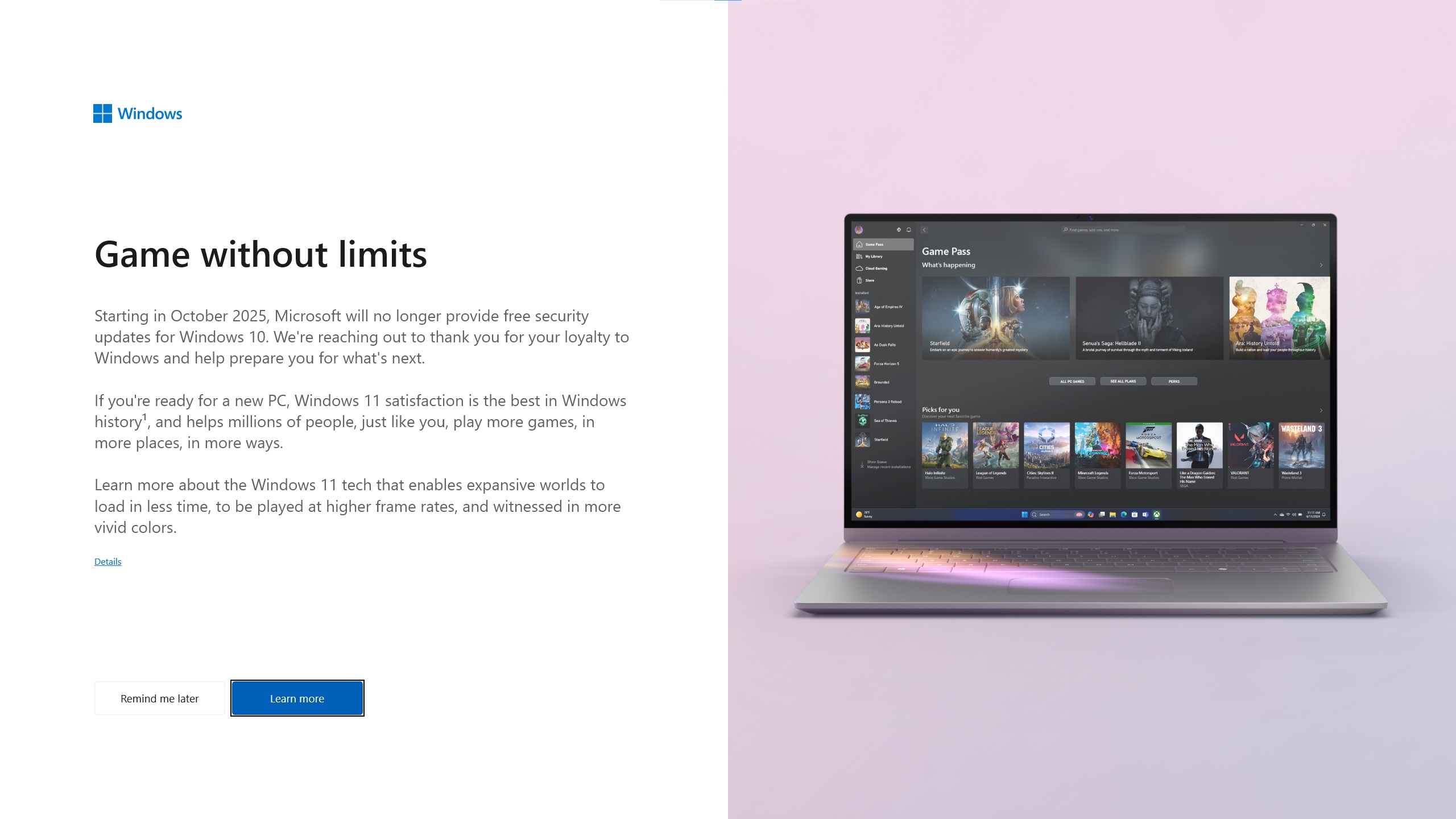

But the requirements don’t feel like something Microsoft has imposed to protect users from threats; they feel like something Microsoft is doing in order to upsell you to a new PC. Microsoft creates that impression when it shows Windows 10 users full-screen ads for new Copilot+ PCs, even when their systems are capable of upgrading to the new operating system directly. People are already primed to believe in “planned obsolescence,” the idea that the things they buy are designed to slow down or fail just in time to force them to buy new things; pushing people to throw out functioning PCs with full-screen ads does nothing to dispel this notion.

Windows 11 could still be great

I still believe that Windows 11 has good bones. Install the Enterprise version of the operating system and you’ll get a version with much less extra cruft on top of it, a version made to avoid alienating the businesses that pay good money to install Windows across large fleets of PCs. Microsoft has made huge strides in getting its operating system to run on Arm-based PCs. The Windows Subsystem for Linux is better than it’s ever been. I’m intrigued by the company’s efforts to make Windows a better operating system for gaming handhelds, Microsoft’s belated answer to Valve’s Steam Deck and SteamOS.

But as someone with firsthand experience of every era of Windows from 3.1 onward, I can say I’ve never felt as frustrated with the operating system as I have during Windows 11’s Copilot era. The operating system can be tamed with effort. But the taming has become an integral part of the new PC setup process for me, just as essential as creating the USB installer and downloading drivers and third-party apps. It’s something my PC needs to have done to it before it feels ready to use.

Windows 10 was far from perfect. But as we mark the first stage of its multi-year passing, it’s worth remembering what it did well and why people were willing to install it in droves. I’d like to see Microsoft recommit to a quieter, cleaner version of Windows that is more willing to get out of the way and just let people use their computers the way they want, the same way the company has tried to recommit to security following a string of embarrassing breaches. I don’t have much hope that this will happen, but some genuine effort could go a long way toward convincing Windows 10-using holdouts that the new OS actually isn’t all that bad.

-

C114 Communication Network

C114 Communication Network -

Communication Home

Communication Home