Credit: Alex Goy

In mid-2022, when BYD executive Lian Yubo was asked to compare Chinese manufacturing with Tesla’s technology, he remarked that Elon Musk was an example that all Chinese carmakers could learn from.

“Tesla is a very successful company no matter what. BYD respects Tesla and we admire Tesla,” he said in an interview on Chinese state media.

Yet just three years later, Tesla’s technological lead over its Chinese rivals has narrowed dramatically. It is fighting to stay ahead in the world’s largest car market, its sales are falling in many other countries and its efforts to develop fully self-driving vehicles are running into regulatory roadblocks.

Having once scoffed at the idea that BYD could ever be a competitor to Tesla, Musk returned from a visit to China last year with a sombre assessment for his senior management. “He had seen the BYD factories, the cost and their tech,” says one former Tesla executive, adding that Musk believed China was winning the electric vehicle race.

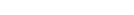

As Tesla’s sales decline following Musk’s forays into US politics and amid a lack of new models, BYD has overtaken it to become the world’s largest manufacturer of EVs. Its annual revenues surpassed $100 billion for the first time in 2024.

Now, the industry’s shift towards autonomous vehicles and artificial intelligence is writing a new chapter in what has become not just a rivalry between the world’s top two EV makers, but a central pillar of US-China technological competition.

“In the west, Tesla still owns EVs, they still have a clear lead on software-defined vehicles and everyone is still trying to catch up to that,” says Barclays analyst Dan Levy. “China is a different situation. Tesla’s lead from a tech perspective is not nearly as clear, if there’s any lead at all.”

Credit: FT

Until recently, the main advantage Chinese EV manufacturers had over Tesla was that their products were significantly cheaper. But in February, BYD’s founder Wang Chuanfu stood on stage in Shenzhen and unveiled “God’s Eye,” an advanced driver-assistance system that is a precursor to fully autonomous vehicles.

A month later, Lian, who now heads BYD’s automotive engineering research institute, was on stage with Wang to announce a new battery charging system capable of adding a driving range of about 470km in five minutes—a fraction of the time it would take a Tesla to charge to that level.

The startling technological advances made by BYD and others have sparked panic among legacy carmakers, who have responded by partnering with Chinese rivals to learn how to build vehicles faster and cheaper, and with better software.

Mark Greeven, professor of innovation and strategy at IMD in China, says Musk “took his eye off the ball” just as Wang progressed from battery technology to software and chip development.

“Tesla did fall back . . . BYD clearly used that time to catch up and say, ‘We’re going to invest in a set of capabilities that are going to make us competitive in the long term.’”

But the man who forced an entire global industry to take electric propulsion seriously is not about to give up. In May, Musk stepped down from his US government role to focus on advancing Tesla’s new growth areas: autonomous vehicles, AI, robotaxi services and a humanoid robot called Optimus.

He says the new products will spur Tesla to become the most valuable company in the world, with a market capitalisation in the tens of trillions.

“His reasoning is: will car companies exist in 10 years without autonomy?” says the former executive. “Probably not, like flip phones versus the iPhone.” With the race to commercialise EVs almost over, he adds that “Tesla has to win in AI and autonomy.”

The chairman

Known within BYD simply as “the chairman,” the 59-year-old Wang used his obsession with batteries to enter car manufacturing in the early 2000s.

Having attracted investment from Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway in 2008, he oversaw a period of staggering growth for the Chinese group, which sold 4.27 million vehicles last year, nearly 10 times as many as in 2020. Of that total, 1.76 million were pure EVs.

Over the same four-year timeframe, Tesla’s sales went from just shy of 500,000 vehicles to 1.79 million—but BYD is in pole position to overtake Tesla in annual global EV sales for the first time in 2025 as it expands overseas.

Electric cars on display at a BYD showroom in Shanghai. The automaker has introduced around 100 cost-saving methods for a range of car components and materials.

Credit: Robert Way via Getty

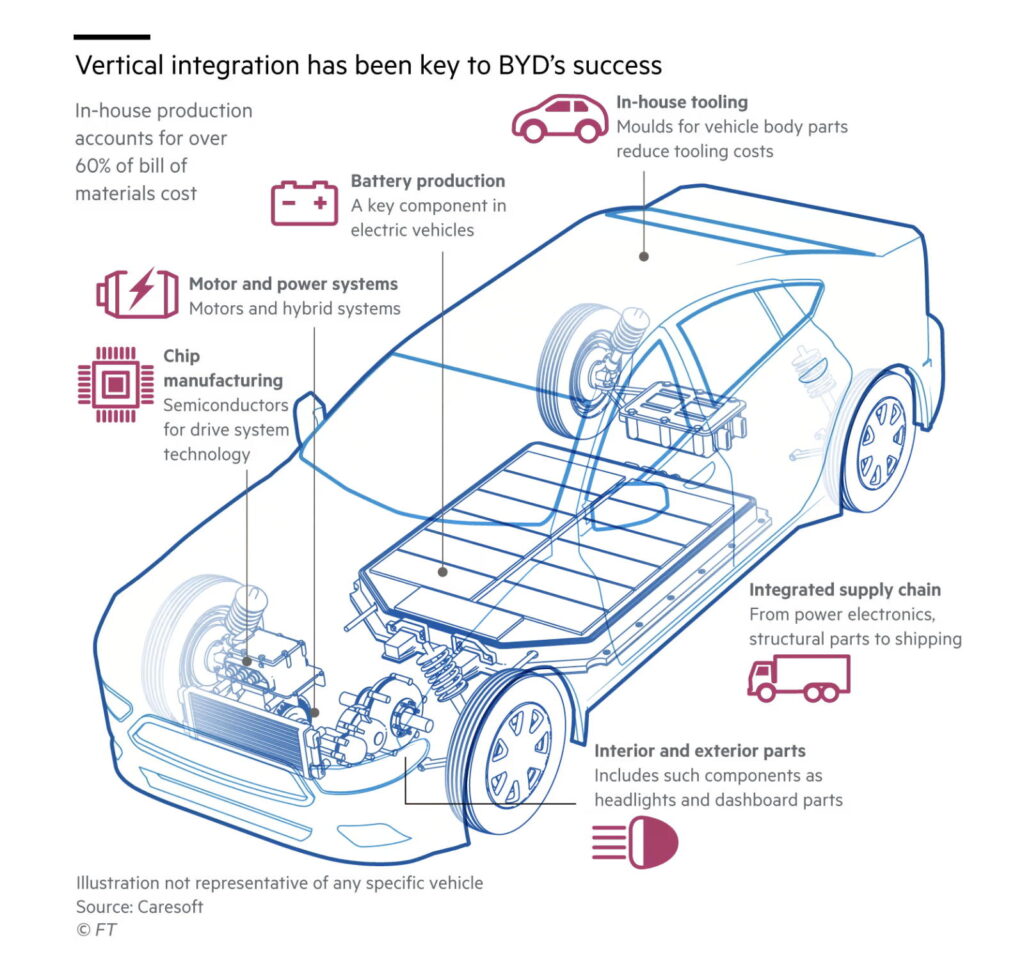

In China it now commands a 21 percent market share, according to Shanghai consultancy Automobility. Tesla, the company credited for sparking consumer interest in electric vehicles when it brought its first model to China in 2013, holds 8 percent.

The success of BYD has come to symbolise the rise of Chinese auto manufacturing, an industry that was once heavily reliant on foreign partners such as Volkswagen, Toyota and General Motors for design and manufacturing know-how.

While other western carmakers were compelled to form joint ventures with local groups, China changed its investment rules to allow Tesla to fully own and operate its Chinese subsidiary. The government reasoned that Tesla’s presence—via two massive plants to build its Model Y saloon and battery packs in Shanghai—would help its domestic infrastructure and supply chain learn and modernise.

Tesla accepted the risk of hardware and intellectual property being transferred, but concluded it was worth it in order to gain access to a huge new market, according to a person familiar with its negotiations.

Yet the speed with which Chinese carmakers learnt and innovated enabled them to leave some of their European and Japanese rivals behind in the EV transition, according to Mathew Vachaparampil, chief executive of Caresoft, a specialist in cost reduction engineering.

“While the legacy manufacturers in Europe, the US and Japan say [Tesla’s] technology will not work in their vehicles, the Chinese say Elon Musk is the leader,” Vachaparampil says. “They are now not only copying Tesla’s technology, but improving it very quickly.”

Credit: FT

Gigacasting, a method of casting and pressing fully formed chassis parts instead of welding together smaller components, is a good example. The process, which reduces vehicle weight, cuts manufacturing times and reduces labour costs, relies on a specially formed aluminium alloy developed by engineers at SpaceX, another Musk company.

It was introduced for Chinese-made Model Y sports utility vehicles in 2021. But according to Caresoft analysis, by the time China’s Xpeng released its G6 SUV in 2023, it had already adopted a gigacasting system that was both lighter and more rigid than the one used by Tesla.

Xpeng and many other Chinese brands have also improved on Tesla’s lightweight, aluminium-made cables for charging and coolant pumps inside EVs. During the Shanghai auto show in April, BYD showcased a premium Denza Z concept car featuring an advanced steer-by-wire system—first introduced by Tesla in the Cybertruck.

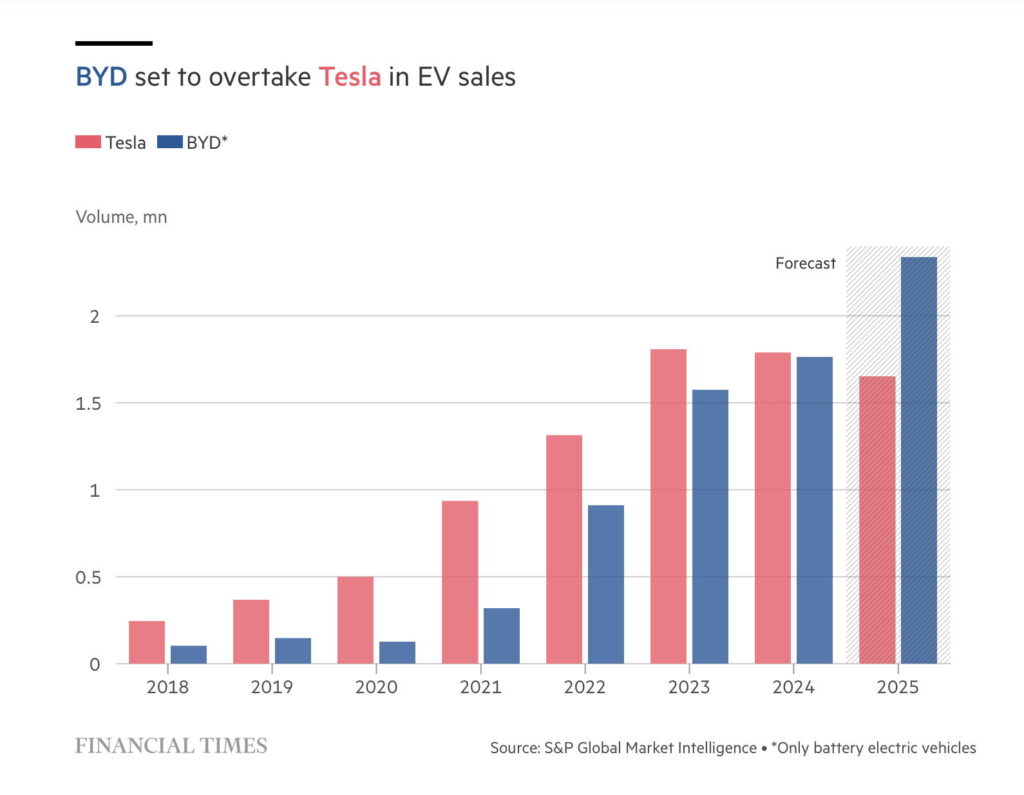

Chinese manufacturers have made innovations of their own, too. According to Caresoft, BYD has introduced around 100 cost-saving methods for a range of car components and materials that, if Tesla adopted, would save between $350 and $885 per vehicle. Alternatively, BYD could also save up to $1,860 per vehicle if it applied some of Tesla’s ideas used in its brake system and heat-exchanger equipment.

Lizzi Lee, a fellow at the Asia Society Policy Institute’s Center for China Analysis, notes that China’s manufacturing ecosystem, including years of investment in infrastructure, supply chain clustering and engineering talent, has “created the conditions” for BYD to succeed.

“That tightly knitted production chain allows it to iterate faster, cut costs more effectively, and maintain a resilient supply chain,” she says.

Software is key, Tesla says

Tesla believes that it still has significant advantages over Chinese rivals in areas such as automation technology, AI infrastructure, access to the latest Nvidia chips and billions of hours of driving video to train its neural network.

“It’s relatively easy to steal or mimic hardware IP,” says one person close to Tesla. “It’s almost impossible to reverse-engineer our software.”

Musk’s biggest ambition in the short term is to deliver Tesla’s self-driving robotaxis at scale following a limited launch in its home city of Austin. While analysts have cautioned that it will be a challenge for Tesla to catch up with frontrunners such as Google’s Waymo, Musk claims the pivot to robotaxis and AI alone could take the company’s valuation as high as $5 trillion.

Elon Musk’s biggest ambition in the short term is to deliver Tesla’s self-driving robotaxis at scale following a limited launch in its home city of Austin.

Credit: Mike Blake/Reuters

“I don’t see anyone being able to compete with Tesla at present,” he told investors in April. “As far as I’m aware, Tesla will have, I don’t know, 99 percent market share or something ridiculous.”

The company’s roughly $1 trillion market value suggests investors believe him. Meanwhile BYD, despite its success providing a wide range of affordable EVs, is not viewed as a software-focused group and, at around $140 billion, is not valued like one either. Its core strength is still perceived as stemming mostly from Wang’s deep commitment to battery technology.

The God’s Eye announcement marked a big shift from Wang, who had previously resisted following domestic rivals like Xpeng and Nio in self-driving technology amid questions over safety. Suddenly, BYD was in the game.

Early versions of the technology are not as advanced as Tesla’s fully self-driving system, offering only basic functionality such as highway navigation and lane changing. But BYD plans to offer God’s Eye in most models at no additional cost, a move analysts say could jeopardise Tesla’s plans to seek a premium for its FSD-equipped vehicles.

Tu Le, a founder of Sino Auto Insights, a consultancy, says the key is not what BYD offers now but the volume of data being collected, which could put it in a position to “win” the race for driverless cars. Each one of the 4.3 million vehicles that BYD sells each year will soon be collecting data to train the company’s algorithms.

Credit: FT

Its size also allows BYD to secure competitive pricing for Nvidia chips that are used in its system, and enables it to provide semi-autonomous features often reserved for premium EVs in its Rmb70,000 ($9,600) budget hatchbacks.

Tesla’s monthly sales in China are much lower than BYD’s, and fell by around 5 percent in the first six months of 2025. But brand damage stemming from Musk’s political activism is not the cause, according to one current Tesla executive.

“Now if you show up with a Tesla and not BYD when there is a de facto ‘buy Chinese’ rule, you have to explain. People don’t want to do that,” the executive says. “Also, the Chinese cars are better.”

However, the bigger challenge for Tesla is China’s restrictions on data collection and transfer. FSD is based on a machine learning system that uses billions of hours of video to train an algorithm to make driving decisions in real time.

Musk has said China does not permit Tesla to transfer driving video generated from its Chinese fleet outside the country, while the US authorities also will not allow Tesla to do training in China. That has in effect resulted in a twin-track learning process, with the Chinese iteration of FSD inevitably having inferior performance because fewer vehicles feed data into it.

According to Duo Fu, a vice-president at Rystad Energy, a Norway-headquartered consultancy, FSD in China is much more reliant on simulations as opposed to real-life human driving experience.

“Tesla has partnered with Baidu [a Chinese search and AI group] but Baidu can’t disclose all the data points to Tesla,” Duo adds. “The real-world data is definitely more valuable.”

Home field advantage

While BYD might have home turf advantage when it comes to data collection and security, Wang’s late pivot to driverless functionality has created some risks for the group.

One is question marks over financial sustainability. Price wars among Chinese carmakers are putting margins and the industry’s balance sheet under strain as Beijing demands more action to protect suppliers in the world’s largest car market.

It has also opened up some rare gaps in BYD’s otherwise formidable vertical integration. Its market leadership has also enabled it to pressure suppliers for price cuts and extended payment terms, allowing it to rigorously control costs.

But according to Chris McNally, an analyst with US investment bank Evercore, the God’s Eye platform uses software and hardware partners, including Momenta, a Chinese group backed by General Motors in the US, and some chips from Nvidia.

BYD’s executive vice-president Stella Li said competition with Tesla in EVs and autonomous technology would accelerate innovation, ultimately making BYD a "better’" company.

Credit: Joel Saget/AFP/Getty Images

For years, the risks associated with reliance on US-made chips in particular have hovered over the Chinese car sector—plans for driverless systems could be held back at any moment by US export controls or sanctions.

“Given the geopolitical environment, no one will invest in a technology with such a high risk that they’re still relying on foreign technology,” says Raymond Tsang, an automotive technology expert with Bain in Shanghai.

However, these vulnerabilities might not persist. Analysts believe BYD will soon develop most of its driverless systems in house and increasingly swap out Nvidia chips for those made by Beijing-based Horizon Robotics. “This is the BYD way to drive costs down,” McNally says.

It would also be consistent with a broader shift towards self-reliance in key technologies, in response to Washington’s steadily increasing restrictions on technology exports to China.

Yuqian Ding, a veteran Beijing-based auto analyst with HSBC, says that while BYD has not talked about developing a robotaxi service, executives have made “very clear” their plans to develop in-house all the important software and hardware needed for autonomous vehicles.

Wang, the BYD boss, has also previously indicated to analysts that the company has all the tech and know-how to develop robots, in another potential long-term challenge to Musk.

“With more than 5 million scale per annum, they can do everything,” Ding says, adding: “That’s the ultimate goal . . . Their target is much closer to Tesla.”

In an interview with the Financial Times this year, BYD’s executive vice-president Stella Li said competition with Tesla in EVs and autonomous technology would accelerate innovation, ultimately making BYD a “better” company.

“In the future, if you are not producing an electric car, if you’re not introducing technology in intelligence and autonomous driving, you will be out,” she warned.

Additional reporting by Gloria Li in Hong Kong

Graphic illustration by Ian Bott and data visualisation by Ray Douglas

© 2025 The Financial Times Ltd. All rights reserved Not to be redistributed, copied, or modified in any way.

-

C114 Communication Network

C114 Communication Network -

Communication Home

Communication Home