Credit: Volvo Cars

With the launch of its all-new, all-electric EX60, Volvo has put lessons learned from the EX30 and EX90 to use. The EX60 is built on Volvo’s new SPA3 platform, made only for battery-electric vehicles. It boasts up to 400 miles (643 km) of range, with fast-charging capabilities Volvo says add 173 miles (278 km) in 10 minutes. Mega casting reduces the number of parts of the rear floor from 100-plus to one piece crafted of aluminum alloy, reducing complexities and weld points.

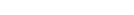

Inside the cabin, however, the real achievement is Volvo’s new multi-adaptive safety belt. Volvo has a history with the modern three-point safety belt, which was perfected by in-house engineer Nils Bohlin in 1959 before the patent was shared with the world. Today at the Volvo Cars Safety Center lab, at least one brand-new Volvo is crashed every day in the name of science. The goal: to test not just how well its vehicles are protecting passengers but what the next frontier is in safety technology.

Senior Safety Technical Leader Mikael Ljung Aust is a driving behavior specialist with 20 years under his belt at Volvo. He says it’s easy to optimize testing toward one person or one test point and come up with a good result. However, both from the behavioral perspective and from physics, people are different. What’s not different, he points out, is how people drive.

“We’re shaped into a very similar automated behavior when we drive, so that makes the collision prevention side of things a bit easier,” Ljung Aust says. “But on the injury-prevention side of things is where the seat belt comes in, we’re working on the principle of equal safety for all. The idea is that independent of who you are in terms of size, shape, weight, all of these things, you should have exactly the same protection.”

No other automaker has the same commitment to road safety as Volvo.

Credit: Volvo Cars

How it works

Basically, a seat belt is made up of a retractor mechanism, buckle assembly, webbing material, and a pretensioner device. Of these parts, the pretensioner is the one tasked with tightening the seatbelt webbing in a collision. As such, it reduces the forward movement of the passenger before the airbag deploys at speeds of up to 200 mph (321 km/h). All of these parts remain the same for Volvo’s newest seat belt iteration. It’s the tiny brain attached to the assemblage that’s different.

Volvo’s new central computing system, HuginCore (named after a bird in Norse mythology), runs the EX60 with more than 250 trillion operations per second. It has been developed in-house, together with its partners Google, Nvidia, and Qualcomm.

“With the HuginCore system we can collect a lot of data and make decisions in the car instantly and combine that with the belt’s ability to choose different load levels,” says Åsa Haglund, head of the Volvo Cars Safety Center. “A box of possibilities opens up where you can detect what type of crash it is and who is in the car and choose a more optimal belt force.”

Every day, dummies like these get smashed to make Volvos safer.

Credit: Volvo Cars

Load limiters control how much force the safety belt applies on the human body during a crash. Volvo’s new system pushes the load-limiting profiles from three to 11, marking a major increase in adjustability. It’s kind of like an audio system, Ljung Aust muses. A sound system with 10 discrete steps up the volume ladder offers varied profiles along the way, while one with only one or two steps addresses fewer preference levels.

Using data from exterior, interior, and crash sensors, the car reacts to a collision in milliseconds—less than the blink of an eye, Ljung Aust says. In the case of a crash, it’s critical to hold the hips into the car, he explains, but the upper body should fold forward in a frontal crash in a nice, smooth motion to meet the airbag. Otherwise, the body is exposed to the same force as the slowing car.

Tempering that motion means adjusting for the size of the passenger to avoid injury; for instance, if the sensors detect a larger occupant in a severe crash, it’s designed to reduce the risk of head injury by using a higher belt load setting. Conversely, a smaller passenger in a lesser fender bender gets a lower belt load setting to reduce the incidence of rib fractures. Haglund notes that while one might make assumptions about what body type is more vulnerable in a crash, it has more to do with the kind of crash itself.

Mechanical engineering plus over-the-air updates

There is no one-size-fits-all approach to crash safety, but the multi-adaptive seat belt is a closer step toward individual protection. Ljung Aust likens the new seat belt system to an octopus; the “tentacles” are the sensors that feed information to the brain. From there, the processor collects the data that Volvo uses to make improvements over time. Over-the-air updates will send future improvements to the car’s HuginCore system.

Volvo introduced the first rear three-point belts in 1972. Wearing a seatbelt in the back of a car still isn’t mandatory in all 50 US states, in 2026.

Credit: Volvo Cars

The timing is where artificial intelligence plays a big part. For every crash, there is an optimal set of outcomes to trigger the belt force. The result needs to happen like that, he says with a snap of his fingers.

Modern safety belts use load limiters to control how much force the safety belt applies on the human body during a crash. But with the new safety belt’s expanded load-limiting profiles, it can optimize performance for each situation and individual. “What is changing is the level of sophistication in how we act on that information,” Ljung Aust says. “We can now be more nuanced with the forces we apply to keep you under the lowest pressure possible [in a crash].”

Not enough people know how a seat belt works, says Ljung Aust, and they should.

“If you find out how it works, you realize it’s pretty cool and it actually makes a difference,” he says. “And to the extent that you were not inclined to wear it before or not be happy about it, maybe that has a positive influence on your attitude. Having a seat belt is literally the best thing you can do.”

-

C114 Communication Network

C114 Communication Network -

Communication Home

Communication Home