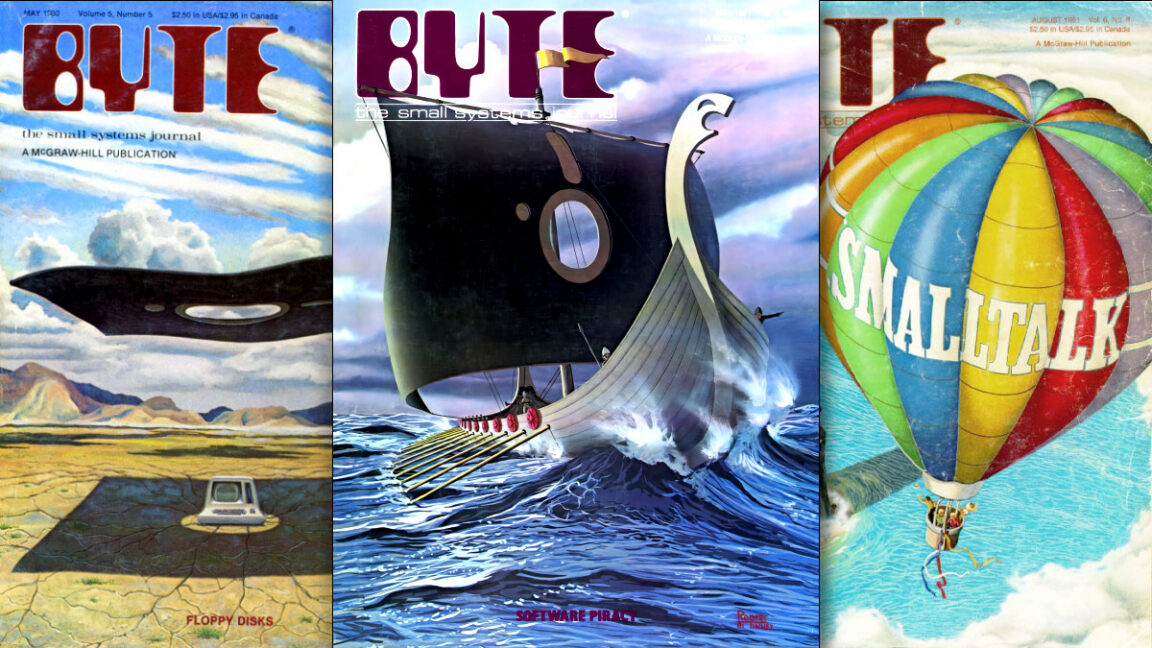

Credit: Robert Tinney / Byte Magazine

On February 1, Robert Tinney, the illustrator whose airbrushed cover paintings defined the look and feel of pioneering computer magazine Byte for over a decade, died at age 78 in Baker, Louisiana, according to a memorial posted on his official website.

As the primary cover artist for Byte from 1975 to the late 1980s, Tinney became one of the first illustrators to give the abstract world of personal computing a coherent visual language, translating topics like artificial intelligence, networking, and programming into vivid, surrealist-influenced paintings that a generation of computer enthusiasts grew up with.

Tinney went on to paint more than 80 covers for Byte, working almost entirely in airbrushed Designers Gouache, a medium he chose for its opaque, intense colors and smooth finish. He said the process of creating each cover typically took about a week of painting once a design was approved, following phone conversations with editors about each issue’s theme. He cited René Magritte and M.C. Escher as two of his favorite artists, and fans often noticed their influence in his work.

A phone call that changed his life

A recent photo portrait of Robert Tinney provided by the family.

Credit: Family of Robert Tinney

Born on November 22, 1947, in Penn Yan, New York, Tinney moved with his family to Baton Rouge, Louisiana, as a child. He studied illustration and graphic design at Louisiana Tech University, and after a tour of service during the Vietnam War, he began his career as a commercial artist in Houston.

His connection to Byte came through a chance meeting with Carl Helmers, who would later found the magazine. In a 2006 interview I conducted with Tinney for my blog, Vintage Computing and Gaming, he recalled how the relationship began: “One day the phone rang in my Houston apartment and it was Carl wanting to know if I would be interested in painting covers for Byte.” His first cover appeared on the December 1975 issue, just three months after the magazine launched.

Over time, his covers became so popular that he created limited-edition signed prints that he sold on his website for decades. “A friend suggested once that I should select the best covers and reproduce them as signed prints,” he said in 2006. “Byte was gracious enough to let me advertise the prints when they could fit in an ad (it did get bumped occasionally), and the prints were very popular in the Byte booth at the big computer shows, two or three of which my wife, Susan, and I attended per year. When an edition sold out, I then put the design on a T-shirt.”

Byte stopped commissioning Tinney’s cover art around 1987, opting for product photographs as competition in the computer magazine market intensified. His final cover was for the magazine’s 15th Anniversary issue in September 1990.

Computing’s Norman Rockwell

What made Tinney’s work distinctive was the fact that he was not a technical person. He had no engineering background and said in the 2006 interview that he always felt “a little uneasy” around Byte’s editors because he didn’t speak their technical language. But he saw that as a strength. “I’ve always thought that my interpretation of computer issues with non-technical visual metaphors was what gave my illustrations their distinctive character,” he told me. “So maybe that was a case of making lemonade out of lemons.”

That approach produced images that communicated instantly: a train running on a printed circuit board for an issue about computer engineering, a tiny computer wristwatch, or robots hatching from eggs. His 1981 Smalltalk cover featuring a colorful hot air balloon, according to his website, became a widely recognized symbol of object-oriented programming.

A collage of classic Byte magazine covers featuring illustrations by Robert Tinney.

Credit: Robert Tinney / Byte Magazine

After leaving Byte, Tinney created illustrations for electronics companies, including JDR Microdevices and Jameco Electronics, and created cover art for Borland’s Turbo Prolog and Turbo Basic software. He eventually transitioned to oil portraits and adopted Photoshop for commercial work. “Anything I can do with gouache and an airbrush, I can do about three times better with Photoshop,” he told me, “plus I don’t have to breathe the fumes!”

Tinney is survived by his wife of 48 years, Susan, and their three children, nine grandchildren, and one great-grandchild. A celebration of his life will be held in May 2026.

In his later years, Tinney grew philosophical about the future of illustration as a profession, noting that stock image databases had changed the economics of the field. But he remained upbeat about the value of artistic talent, comparing it in that 2006 interview to the skill of public speaking: “It’s a nice talent to have, but it isn’t easy to find someone who’ll pay you just to do it. You need to combine that basic talent with another skill to really have a marketable service.”

-

C114 Communication Network

C114 Communication Network -

Communication Home

Communication Home