(Image credit: Tom's Hardware)

-

Facebook -

X -

-

-

Flipboard

Choosing the right CPU is critical when you’re building a new PC. If you’re wondering which CPU to buy, our CPU benchmark hierarchy goes in-depth on our latest benchmark results, and our roundup of the best CPUs for gaming offers our current recommendations, taking into account pricing, performance, and efficiency. Even with those resources, choosing the right CPU is a complex topic with a lot of moving parts.

AMD and Intel both make excellent processors, and there are reasons to pick up something as weak as the Core i3-14100F all the way up to the Ryzen 9 9950X3D, depending on your purpose. Here, we’ll walk you through how to make that decision, as well as give you some broad pointers on how to parse CPU naming conventions and specs.

AMD and Intel are currently winding down their respective generations. AMD has built out a broad lineup of Ryzen 9000 CPUs based on the Zen 5 architecture, and Intel has confirmed that it will reuse its current-gen Arrow Lake architecture with a refresh of CPUs dubbed Core Ultra 300-S. Intel has also confirmed it will move beyond Arrow Lake to the new Nova Lake architecture in late 2026, and AMD is working on its next-gen Zen 6 architecture, but without a firm timeline.

- The Best CPU for Gaming

- Intel vs AMD

- CPU Hierarchy

- Best CPU Deals

- AMD Ryzen 7 9800X3D vs Intel Core Ultra 9 285K Faceoff

- The Best GPU for Gaming

- All CPU Content

How to choose a CPU – the TL;DR

(Image credit: Tom's Hardware)

When you’re shopping or choosing between different CPUs, there are some broad ideas to keep in mind.

- Budget for your build and purpose – A CPU does nothing on its own, so define your budget in the context of a full system and what you intend to use that system for. That might mean settling on a slightly less powerful (but cheaper) CPU for a gaming system and reallocating that money toward a more powerful GPU, for example. If you’re on a tight budget, our ranking of the best budget CPUs can help.

- Performance only tells part of the story – Performance benchmarks are critical, but they need context. Efficiency, temperatures, overclocking headroom, and architectural features play a role in the CPU you should buy, which we dig into in our individual CPU reviews. Further, certain benchmarks aren’t relevant to every buyer. The Core i9-14900K may blow away the Ryzen 7 9800X3D in video transcoding, for example, but if you’re not transcoding any videos, that performance vector hardly matters.

- AMD and Intel are both good – Some enthusiasts prefer one brand over the other, but there are plenty of reasons to buy an Intel CPU over an AMD one or vice versa. Our Intel vs AMD faceoff will get you up to speed on where the brands currently stand, but there’s no reason to play favorites for the sake of doing so.

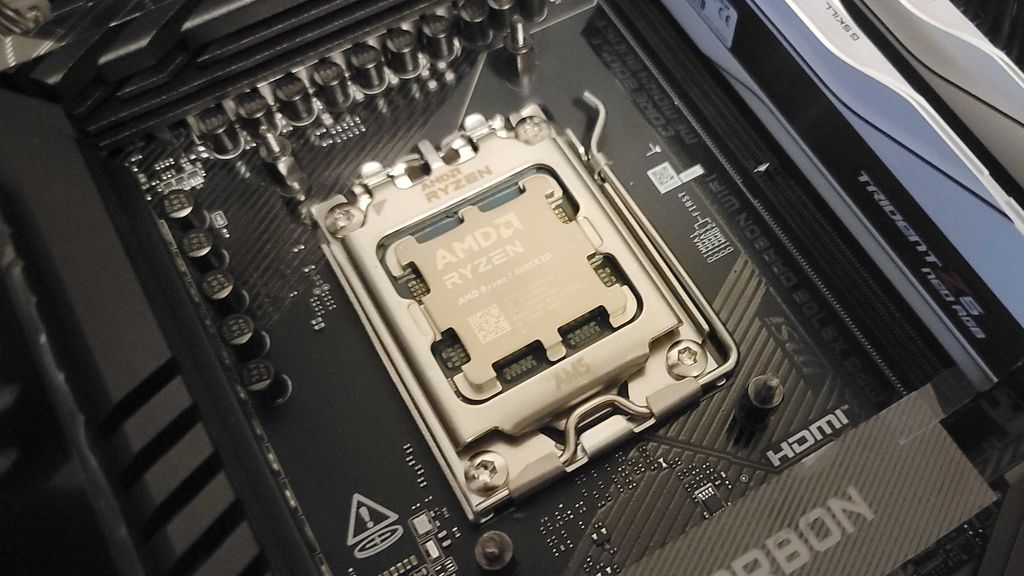

- Trust data, not lineups – AMD and Intel segment their CPU lineups so it’s easy to spot a more powerful CPU over a weaker one. These gaps aren’t made equally, however. For instance, the Core Ultra 7 265K offers 98% of the gaming performance of the Core Ultra 9 285K (functionally identical), despite the Core Ultra 9 costing around $200 more. Performance doesn’t scale linearly across a lineup.

- Architecture informs specs, not the other way around – Specs are important, but they start to fall apart when comparing CPUs from distant generations. The Ryzen 9 3950X and Ryzen 9 9950X both have 16 cores and 32 threads, and the Ryzen 9 9950X has a 21% faster clock speed. The Ryzen 9 9950X isn’t just 21% faster, though; it’s often twice as fast or even faster in productivity applications.

We’ll walk you through how to understand CPU names, specs, and prices, as well as how to put them all together to choose a CPU for your specific purpose. We’ll also take a look at the motherboard chipsets available this generation, as well as overclocking and how it plays into a buying decision.

How much you should spend on a CPU

(Image credit: Tom's Hardware)

Ignoring the secondhand market, you can spend anywhere from $50 to over $700 on a consumer CPU. You can spend even more with something like AMD’s Threadripper range, with a chip like the Threadripper 9980X selling for $5,000. It’s important to define the purpose of your CPU so you know how much you should spend.

There are exceptions to any rule, but CPU prices break down into a few broad categories.

- Basic use ($50 to $100) – For basic PC use, including browsing the internet and running lightweight office applications. CPUs in this bracket include the AMD Ryzen 5 5500 and Intel Core i3-14100F.

- Budget ($100 to $200) – More performance to power light gaming and slightly more intensive productivity apps. CPUs in this bracket include the Core i5-12400F and Ryzen 5 7600.

- Midrange ($200 to $350) – The sweet spot for gaming PCs, with enough power to run content creation apps. CPUs in this bracket include the Core Ultra 7 265K and Ryzen 7 9700X.

- High-end ($350 to $500) – Plenty of power for gaming, but a stronger emphasis on accelerating productivity and content creation apps with high core counts. You’ll find specialty chips like the Ryzen 7 9800X3D in this bracket, as well as previous-gen flagships like the Core i9-14900K.

- Flagship ($500+) – The fastest processors in a given generation. You won’t see much of a boost in gaming performance, with flagships focusing almost solely on accelerating productivity applications with the highest core counts, clock speeds, and power consumption. CPUs in this bracket include the Core Ultra 9 285K and Ryzen 9 9950X.

That should give you an idea of how much you should spend on a CPU. If you want to build a gaming PC, you’re probably focused in the midrange or high-end brackets. If you will regularly edit and transcode videos, however, you’re probably focused on the high-end to flagship range.

Understanding CPU names

(Image credit: Tom's Hardware)

AMD and Intel use slightly different naming conventions, but they follow the same template. Here’s how that broadly breaks down for desktop CPUs:

- Segment – Ryzen 5, Core Ultra 5

- Series – First number in model name, i.e. Core Ultra 5 245K, Ryzen 5 9600X

- Model – Numbers following the series number, i.e. Core Ultra 7 265K, Ryzen 7 9700X

- Modifier (Suffix) – Letter following model number, i.e. Core Ultra 5 245KF, Ryzen 7 9800X3D

that The segment and model numbers speak for themselves; a higher number is better. A Ryzen 9 sits above a Ryzen 5, and the Core Ultra 5 245K sits above the Core Ultra 5 225. The two tricky parts are the series and modifier, which is where a slight misunderstanding could lead to a vastly different CPU.

First, series: You may read that the first number in the model string refers to the architecture, but that isn’t the case. It’s just a series or generation. AMD and Intel reuse architectures. For instance, Ryzen 7000 ‘Raphael’ and Ryzen 8000 ‘Phoenix’ chips both use the Zen 4 architecture. Similarly, the Core i5-13400F has two versions, one that uses 12th-gen Alder Lake and another that uses 13th-gen Raptor Lake, though thankfully without any notable performance differences.

On desktop, Intel and AMD mostly keep the lines straight. Ryzen 8000 wasn’t a proper generation, for instance; it’s a lineup of APUs that don’t mingle with the main Ryzen 7000 lineup. However, we’ve seen willingness, especially from AMD, to blur the lines between generation and architecture significantly on mobile. It’s good to get the naming convention straight in the event the same happens on desktop.

Suffixes give you a lot of information, but they vary between Intel and AMD. For AMD, here are suffixes you should know:

- X or XT – X-series processors are the main lineup of chips within a particular generation from AMD. The XT designation is used for rereleases of X-series chips with higher clock speeds. On the other end, chips without the X suffix are rereleases with lower power consumption and clock speeds.

- G – CPUs with a G suffix note integrated graphics, particularly for a lightweight gaming APU like the Ryzen 7 8700G. From Ryzen 7000 onward, AMD has included integrated graphics in its main lineup, though they’re significantly weaker than the iGPUs featured in G-series chips.

- F – AMD seldom uses the F suffix, but it notes processors that lack integrated graphics that they’d otherwise have. The Ryzen 5 8400F lacks the integrated graphics that are otherwise available this generation. The Ryzen 7 5800X, however, doesn’t have the F suffix but still lacks integrated graphics.

- X3D – X3D is used to note CPUs with AMD’s gaming-focused 3D V-Cache. Notably, it doesn’t say what generation of 3D V-Cache a chip uses. Ryzen 7000X3D and Ryzen 9000X3D chips, for example, use a different 3D V-Cache design.

Intel has a longer, more rigid lineup of suffixes that it has maintained for decades, making models much easier to parse compared to AMD:

- K – Unlocked for overclocking.

- F – Lacks integrated graphics.

- S – Special edition release.

- T – Low-power design, meant for compact systems.

Thankfully, Intel’s suffixes don’t require much explanation because of how rigid they are. If a processor lacks the K suffix, you can’t overclock it, pure and simple. Intel will combine suffixes when necessary, however. The Core Ultra 5 245KF is unlocked for overclocking but lacks integrated graphics, for example, while the Core i9-14900KS is a special edition of the unlocked Core i9-14900K.

Critical CPU specs to know, and what they mean

(Image credit: Bilibili)

CPU specs are only useful if you understand what they mean – and, more importantly, what they don’t. Unlike generations past, where big clock speed boosts and core count jumps were common, AMD and Intel have much more conservative spec bumps each generation, if there's a spec bump at all.

Specs are still important for neighboring comparisons, but it's important to understand what they mean in the broader context of a CPU's architecture.

Cores/Threads

Why you can trust Tom's Hardware

A CPU with more cores can execute more instructions in parallel, but how that manifests in real applications varies widely. Rendering applications like Blender and transcoding applications like Handbrake scale well with high core counts, for example. Games, on the other hand, don’t see large performance jumps past eight cores, and many games don’t even see a marked improvement beyond six cores.

AMD’s modern CPU cores are designed with simultaneous multi-threading, or SMT. This doubles the number of logical processes running on a physical CPU core. So, the 16-core Ryzen 9 9950X has 32 threads. Intel originally introduced SMT – Intel calls it Hyper-Threading – but its current-gen Arrow Lake CPUs don’t use Hyper-Threading. Each physical CPU core only has a single thread.

Traditionally, CPUs use a homogeneous architecture; each core has the same design. Intel has pushed toward heterogeneous architectures in the past several generations, however, mixing together high-performance P-cores with high-efficiency E-cores within a single CPU. These designs can boost overall core count by leveraging weaker cores instead of high-performance cores across the entire die.

From a shopping perspective, it’s important to keep the heterogeneous architecture in mind for Intel chips. The Core i9-14900K has 24 cores compared to the Ryzen 9 9950X’s 16. However, both chips have 32 threads – the E-cores on the Core i9-14900K lack Hyper-Threading.

Clock Speed (Base/Boost)

Synchronizing the disparate components of a CPU architecture is a clock. Clock speed is a frequency – how many cycles are completed each second – and there are two numbers for a CPU. There’s a base and boost clock speed. In modern CPUs, the boost clock speed generally refers to the maximum clock speed on one or two cores, not the maximum clock speed for all cores operating at the same time. Often, one or two preferred cores will boost to higher speeds and handle heavy-duty calculations while the other cores operate at a lower frequency with less intensive work.

Clock speed is important, but it says less about how powerful a CPU is than it previously did. Critically, clock speed doesn’t say anything about how many instructions are executed per cycle. You can think about clock speed like the speed of a conveyor belt. You can increase the speed of the belt, but it might get too hot and break. Alternatively, you can keep the speed the same and widen the belt, or stack things on top of each other, to move more stuff at the same speed.

Rather than the belt speed, a better number to use would be how many items you're able to move. For CPUs, that number is instructions per clock, or IPC; you’ll also see it referred to as instructions per cycle. There are physical limitations of how high the clock speed can go, but if you're able to get more done with each clock cycle, the CPU runs faster.

IPC is a good indicator of architectural improvements from one generation to another, but you won’t find it listed on a spec sheet.

Cache and cache levels

CPUs execute a lot of instructions very quickly, so it’s important that the data needed for those instructions are close to the cores executing them. That’s your CPU’s cache. It’s a small amount of SRAM located on the package of the CPU. Without cache, your CPU would need to use your system’s DRAM for everything, which is considerably slower and would cause a significant bottleneck in your system. Decades ago, CPUs didn't need cache because the system memory could keep up with the pace of instruction execution. With a modern CPU, constantly going out to system memory would make your PC feel unusable.

Cache is organized into levels, with the lowest-number level being the fastest and smallest. L1 is the smallest and fastest, L2 cache is slightly larger, and L3 cache is larger still. CPU cores generally have dedicated L1 and L2 cache, while the L3 cache is much larger and shared across the cores. More cache is generally better, but there are limitations to how much cache can go on-package. Not only is SRAM expensive, it also takes up precious die space and contributes to heat. That’s why packaging technology like AMD’s 3D V-Cache have been such a breakthrough.

Although cache is important, more cache doesn’t lead to universally higher performance. It contributes to higher performance in applications where new data is flowing through memory frequently, such as in games.

Power and Operating Temperature

Power is a messy topic rife with misunderstandings in the world of CPUs. Generally, you’ll see power consumption shared as the Thermal Design Power, or TDP, of a CPU. However, TDP isn’t a power limit, and it doesn’t refer to power consumption. Rather, TDP refers to how much heat the CPU cooler needs to dissipate under maximum load. More power leads to more heat, so TDP is measured in power instead of temperature.

In use, your CPU will often consume less power than the TDP, and it can consume more power for brief periods of time as long as it stays within its thermal limit. To measure peak power consumption, AMD uses PPT, or Package Power Tracking, to note how much power the CPU socket can draw. Intel uses power levels, noted like PL1 and PL2. PL1 is synonymous with TDP, while higher level power limits show maximum power for transient spikes. For high-end, unlocked SKUs, Intel applies a power profile where PL1 = PL2. That means the CPU can sustain higher power consumption for longer than the specified window, assuming it has adequate access to cooling.

Finally, there’s a maximum safe operating temperature, often referred to as TJMax. Once your CPU hits its maximum operating temperature, it will reduce speeds in order to bring the temperature down. In the event the temperatures can’t drop, built-in safety mechanisms will shut down the PC.

Power is a complex topic, and specs don’t share the full picture of power consumption and operating temperatures. Here at Tom’s Hardware, we run a full suite of power and thermal tests for our CPU reviews, which provide a more accurate insight into what you can expect out of a chip. You should use power and temperature specifications to inform your cooler, case, and fan choices, not as hard and fast rules about power consumption.

Chipsets and sockets

(Image credit: Future)

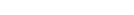

Desktop CPUs are socketed, not soldered, so you’ll need to pick up a motherboard with the socket that matches your CPU. AMD is currently on Socket AM5 while Intel is on LGA 1851. Both are Land Grid Array (LGA) sockets, where the CPU features contact pads that press into spring-loaded pins in the motherboard socket. AMD previously used a PGA, or Pin Grid Array, socket where the pins were on the CPU itself. AMD abandoned this design with the release of Ryzen 7000 CPUs and sunsetting of Socket AM4.

The socket only defines physical compatibility between a CPU and motherboard; the chipset defines full compatibility. Here are the chipsets from AMD and Intel with the latest socket, and the CPUs they support:

| Row 0 - Cell 0 | Chipsets | CPUs |

AMD | A620, B650, B650E, X670, X670E, B840, B850, X870, X870E | Ryzen 7000, Ryzen 9000 |

Intel | H810, B860, Z890 | Core Ultra 200S ‘Arrow Lake’ |

AMD, especially, supports its sockets for several generations even with evolving chipsets. Pairing a newer CPU with an older chipset will generally require a BIOS update. Intel moves from socket to socket faster, but the same rule applies when the same socket is carried across multiple generations of chipsets.

There are a ton of differences between chipsets, but generally, you need a B-series chipset for AMD and a Z-series chipset for Intel. Those are the ranges that offer both memory and CPU overclocking – short of B840, which AMD oddly removed CPU overclocking capabilities from. A/H-series chipsets are for budget builds with limited capabilities, while higher-end chipsets pack features like additional PCIe lanes, and better USB and Wi-Fi capabilities.

The best course of action is to look at the individual motherboard you’re interested in once you’ve settled on a CPU. Chipset specifications aren’t rigid across the board, so you can only know the full capabilities of your motherboard once you have one in mind.

Overclocking and undervolting

(Image credit: Safedisk)

Enthusiasts looking to squeeze the most performance out of their CPU need to keep overclocking (and undervolting) in mind. If you want to overclock your CPU, you’ll need to buy a specific type of CPU and motherboard.

AMD is more friendly to overclocking in that it’s available on nearly all desktop CPUs. There are rare exceptions like the Ryzen 7 5800X3D, but the vast majority of AMD CPUs have direct multiplier-based overclocking. In addition, AMD supports CPU and memory overclocking on both B- and X-series chipsets, short of the B840 chipset.

Intel charges a premium for overclocking capabilities. You need a K-series processor and a Z-series chipset for CPU overclocking.

Regardless of the brand, you can overclock the traditional way through your BIOS, or you can use one-click overclocking features. AMD offers Precision Boost Overdrive (PBO), which you can configure through the Ryzen Master software. Intel has its Extreme Tuning Utility (XTU) that offers easy-to-use dials and a one-click overclocking feature.

Should you overclock your CPU?

When core counts were low and applications were designed for only a handful of threads, there were direct, immediate performance benefits from even a minor overclock. Today, things are different. You can still see a performance boost, but it depends on the application you're using and the CPU you’re overclocking.

A stable, day-to-day overclock is best to bridge small gaps in performance. For example, the Core i7-14700K and Core i9-14900K both come with eight P-cores, but the Core i9 has a higher boost clock speed and four additional E-cores. In applications that care mostly about those eight P-cores, you can get close to the stock performance of the Core i9-14900K with a moderate overclock on the Core i7-14700K on a couple of preferred P-cores.

The benefits of overclocking are dynamic, changing from generation to generation and across different applications, so there are no hard and fast rules on if you should overclock or not. Even if you plan to overclock, you shouldn’t expect lineup-breaking performance differences with modern CPU architectures.

Putting it all together

A CPU is one of the most important components of your PC, but it’s only one component. Once you’ve settled on a processor, make sure to check out our guides on the best SSDs, best RAM, best graphics cards, and best power supplies to pick your other components. Our roundup of the best PC cases can help, too, with modern designs that look as good as they feel to build in.

- MORE: CPU reviews, analysis, and buying guides

- MORE: How to check CPU temperatures

- MORE: How to choose a motherboard

- MORE: CPU price index

- MORE: AMD vs Intel

-

C114 Communication Network

C114 Communication Network -

Communication Home

Communication Home